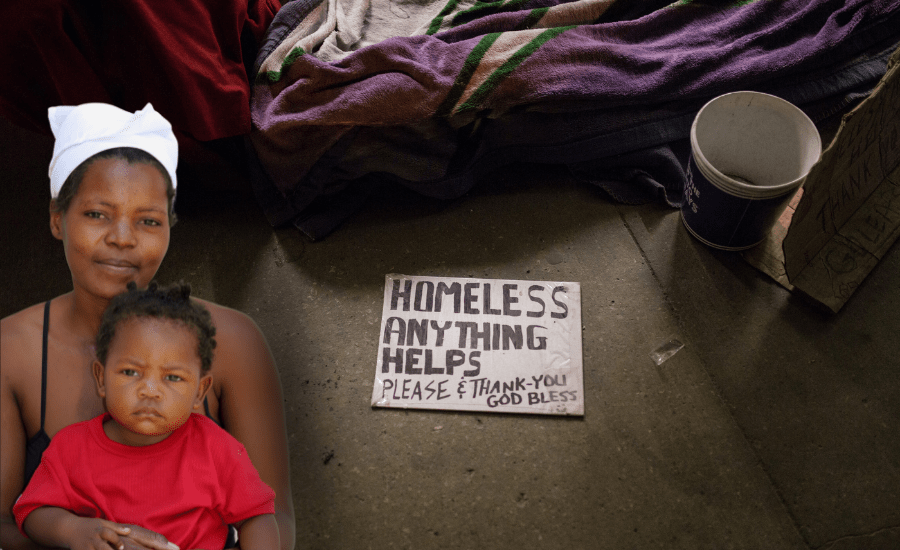

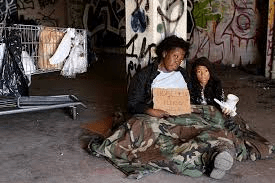

Because there was no room at the inn

the minority report on faith and culture

For most of us, the notorious season known as The Holidays strikes an odd combination of dread and delight. There is so much to do, so many people to see and so many family commitments. Or perhaps there is just a memory of that time, or the absence of family commitments due to distance, death or estrangement. These thirty plus days of the season are a complex thing.

And in the midst of it all we lament that we need to put the Christ back in Christmas.

So we bring out our crèche scenes and deck the halls. We search the traditions and hope that something new might catch our eye and ground us in a different place.

We roll out the familiar stories and wonder what it is we are to believe. Did it really happen that way? Is it just a quaint story? How do we reconcile what we know with what we read? On the one hand we get caught in “What really happened?” On the other hand we dismiss the accounts as stories of people from a simpler time that have no relevance for us in our sophisticated and learned time.

Either way we fail to ask what Marcus Borg suggests is the most important question: what did the stories mean then and what might they mean for us now? Absent our study and prayer, we rob ourselves of what we most need to fill our emptiness and quiet our hubris.

It may be that what is really needed is to put the promise back in the proclamation. Rather than just tell the stories as static episodes of an otherwise forgotten past, we need to receive these ancient stories as promises that can speak in and through our lives.

Much of what holds us and hurts us in these days is how the past, the present and the future collide in our lives. We remember the way it used to be in our families when everyone was there. We remember snow gently falling on Christmas Eve and the happiness of times past. We remember, albeit at times with rose colored glasses. We grieve for what once was and what is no more. We grieve for what never was and measure the distance between the life we dreamed and the life we live.

Wendy Wright writes, “What we all dream, what we all hope for is simple. We dream that the glimpses of the fullness of love that we sense occasionally in our lives show us what we were created to become. When a young father takes his newborn daughter in his arms for the first time, when a mother eases the midnight fears of her frightened son, cradling him and recalling the intimacy of his infant mouth on her breast, when an estranged couple grope their way painfully back into love again, when a family makes a pilgrimage to the bedside of a dying loved one and finds itself bathed in the mystery of love; when a single woman comes to see her solitary dwelling not as a place of emptiness but as a nest sheltered under the wing of God, when a community provides an environment of healing, when friends call us to remember our most authentic selves, when a strange and fearful person becomes for us the face of God, it is then that we begin to sense what we are intended to be. God’s children, the children of promise.” (Wendy Wright, the Vigil p. 23)

What we dream, what we hope for is simple, that the glimpses of the fullness of love that we sense in our lives show us what we were created to become.

The way we put Christ back in Christmas is to start from where we are. To receive the promise into our lives as they are in this moment and to let that promise be seen in us. The promise is for us, and our lives become the proclamation.

The good news and the other news, which is finally good news, is this. This present moment, the good and the not so good, the memories and hopes, and the uncertainties and anxieties are the place where God comes with the good news we so long to hear.

Indeed, the One we celebrate in this season, the life we welcome in Jesus is the one that shows us the path through transformation to wholeness. It’s hard to define wholeness, but it has its root in what we most long for, what we know in our bones is our true home. We were made for love, for life abundant, that what is most important cannot be bought only given and received, that this wild and wondrous journey through our days is more than what we can see.

What changes Christmas and puts the Christ back in it is connecting the promise and the proclamation. It is more than announcing a baby; it is announcing that God is still in this world making this moment new.

It is more than remembering the past, it is proclaiming that God is still in this world healing what was shattered, strengthening what was planted and bringing it together in a new wholeness that is more than the deepest pain or the greatest joy.

It is receiving the promise and then proclaiming it in the way we live.